By Nathan Harnagel

There are times in competitive sports where a team comes out of nowhere and achieves far more than anyone expected. A “Cinderella Season” is one where the previously unknown challengers don’t seem to have anything in their favor and yet they make it into the championships. The appeal of the story is that the new contenders are not from powerhouse programs with massive resources and hand-picked players. I had the chance to participate in one of these underdog teams during the National Championship Air Races in 2016.

The airplane that was the basis for the team was Jet Race-55, a mostly stock Aero Vodochody L-29 Delphin. Delphin means “Dolphin” in English and the airplane has a large cartoon dolphin painted on the nose which appeals to children and draws good natured ridicule from other racers. The airplane was nicknamed “Flipper” and formally named “Spirit of Freedom.” It had been used in previous years by first time entrants into the Jet Class to get experience in the relatively slow Bronze Class before moving up to the faster planes in the Silver and Gold races.

My own experience in jets was limited although I had raced at Reno in the T-6 Bronze Class and had significant formation experience. I was offered the opportunity to attend the Pylon Racing Seminar (PRS) and fly a beautiful Aero Vodochody L-39 Albatros Jet Race-54 for training purposes and to gather research for an article about racing jets.

I had flown the L-39 many years ago but never finished out the rating. I went to Larry Salganek at the Jet Warbird Training Center in Santa Fe and got rated in both the L-29 and L-39. They are the predominant aircraft seen in Jet Racing. There are so many similarities between the L-29 and L-39 that it is very efficient just to complete one rating and move straight away to the next.

The Classic Jets Aircraft Association (CJAA) has a formation clinic prior to PRS and I had the opportunity to attend with Phil Fogg as my instructor flying Bob Miles’ L-39 Race-54 “Robin 1.” I expected the relative rates and different handling characteristics of jet powered aircraft to be totally different from propeller aircraft. The low drag jet airframes usually use deployable speed brakes to precisely control velocity without fighting the slow spool up and down characteristics of their engines. It turned out there were many similarities to other formation flying I had done and the transition was logical and actually fun.

PRS itself combines the challenges of close formation flying with high speeds close to the ground and a narrowly defined course with small pylons and nearly invisible boundaries. Racing Jets Inc. is responsible for the training at PRS and I flew with instructors Phil Fogg, Mike Steiger, and Jeff Turney. Although I had been on the course in 2012 at T-6 speeds, the longer jet course and higher speeds required a rapid increase in mental processing and significantly more physical endurance at the higher G-loads required by jet speeds. Although air racing is not for everyone, you may find the full throttle, hard turning, and split second nature of it exhilarating.

My experience at PRS was enjoyable and successful. When it ended I was invited to come back and compete in September. Now all I needed was an airplane and a team!

I was put in contact with Cliff Magee who currently owns Race-55. Cliff and I talked about my experience and recommendations and he agreed to allow me to race his airplane at Reno. The aircraft had been in storage since the races the year before and we had hopes that it would be pulled out and run prior to my arrival so we could get a chance to do some flying in it before the race qualification period. As it turned out, the aircraft would not be run prior to my arrival.

Where do you find a racing jet team to support you and prep the airplane every day? My team started out with my friend Robert Plunkett who had a friend George Martin. Robert had done ballistic missile maintenance in the Air Force and George had worked on the L-39 and MiG-15, but not the L-29. Add to this to my crew chief from the T-6 racing, Randy Wahlberg, and you have the basis for a small and enthusiastic, but not exactly veteran unit. Don Price joined the team late as polisher/helper/jack of all trades. A rookie pilot and no experience in the specific aircraft to be raced by any of the crew meant there was no reason for optimism. Fortunately, the stories of a brotherhood of racers turned out to be true and we had essential help available from the other racing teams.

There were a number of glitches in the aircraft when we first pulled it out. A flat nose tire and a difficult to diagnose electrical charging issue dogged us early on. Aviation Classics based at Stead airfield helped us with the tire repair and tried to help us with the electrical problem. In the event, I only got a single flight in the aircraft prior to tech inspection. After that I got a single practice flight on the race course prior to the beginning of race qualification.

Qualifying is required for any aircraft to race at the Reno National Championship Air Races (NCAR). In qualifying you go on the race course either by yourself or with a limited number of other racers and run precisely timed laps to get a calculated speed. The speeds run by various aircraft are compared and like aircraft are matched together for heat racing and the Trophy Races at the end. The slowest aircraft are in the Bronze Class and that is usually where you will find all the stock L-29 type aircraft.

Jeff Turney advised not to be too worried about optimum weather conditions and just go get a time so you can race. Somehow I ended up the first jet racer sent on the course to qualify with my total of two flights experience in the airplane. The resulting 411.951 mph was the fastest qualifying time recorded by this airplane in its many years of racing. My crew was overjoyed and I immediately was barraged by other racers with questions of what we had modified to achieve that speed.

The truth is… basically nothing. Racing speed comes from increasing thrust, decreasing drag, reducing weight, and pilot technique around the pylons. Environmental conditions such as temperature and wind turbulence can be inescapable factors and comparing “qual” times from year to year may be tricky and misleading. All we had time to do was get the airplane flying, spray on some Lemon Pledge wax, and use auto store “speed tape” to close up some seams and cover screws. Race-55 had previously had the speed brakes removed to reduce weight and perhaps drag. Some said it would be of no significant help in going faster and just make it harder to control the airplane for the race formation join-up and the line abreast start. The fast qual time actually took us out of the Bronze with our L-29 friends and placed us in class with the Silver racers that are primarily relatively fast L-39s.

Since we were in the Silver, we sat out a day and watched the Bronze racers while wondering if our qual time was some kind of fluke. After the day off our first Heat race resulted in a 414.510 mph speed. This increased the scrutiny on our little team even more. Some said we must have retuned the engine dangerously hot. Protesting that we were not experienced enough with the airplane to retune anything and were just running it the way it had been set up the year before was met with skepticism by some. I talked to my team and directed them to closely examine the engine looking for any signs of distress before and after each race. Other helpful friends immediately offered suggestions of things to take off the airplane to make it even faster! The only factors we really had control of were weight of fuel and pilot technique. As we gained experience with the airplane I was willing to reduce our initial conservative fuel margins for a little more performance. Regulations regarding required fuel reserves were waived by the FAA for the races and we had the freedom to choose based on our own observed burn rates and perceived risk.

The absence of speed brakes did require some special thinking and technique for rapid but controlled join-ups. Also, coming off the course at double the rated landing gear speed with limited options to slow down required some thinking through options and experimentation. The other racers knew of my aircraft’s limitations in this regard and regardless of the order of finish, we safely and promptly sequenced in landings.

Racing these relatively light wing loaded aircraft at high speeds in the turbulence created by wind, thermals, and other aircraft can be compared to a losing effort in a boxing match. You are flying around the course for around seven minutes at generally 4-5 times the force of gravity and frequently being hammered by negative forces strong enough to hit your helmet on the canopy even when you are strapped down as tight as possible by your crew chief and positive forces strong enough to almost double you over at the waist even though you are restrained by a locked shoulder harness.

Our other Heat races resulted in consistent 400+ mph results. The last Heat race had a somewhat slower time of 400.758 mph but it had included several laps where I was on the wing of my old friend from PRS, L-39 Race-54, flown by Jeff Turney. I couldn’t muster the speed to completely pass him but the effort was exciting for me and thrilling for my crew.

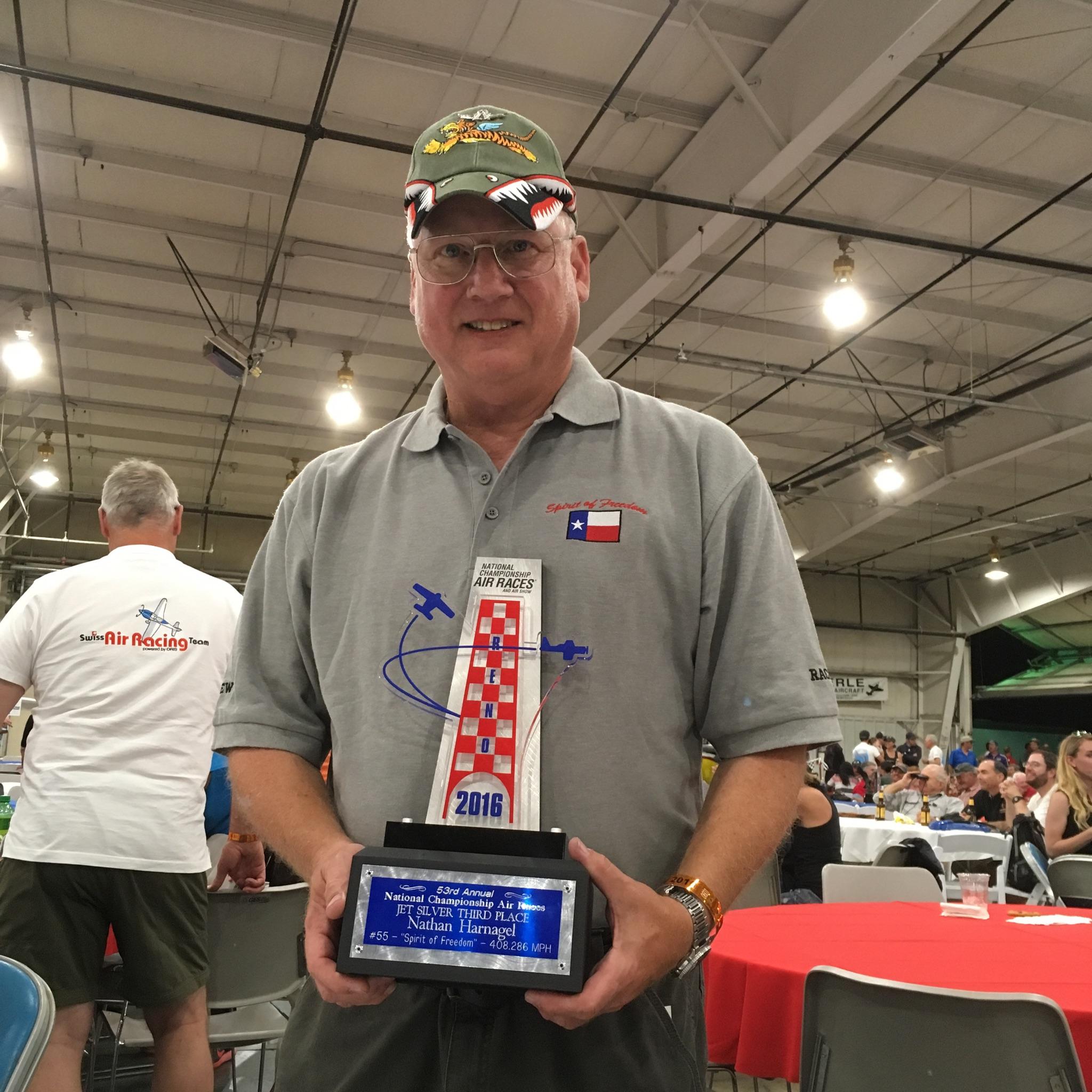

The Trophy Race on Sunday was my last chance to show that our results were not flukes and we really were a consistently above 400 mph competitor. So far we had avoided any cut pylon penalties but I knew there were slight improvements in the line flown that could get a few mph improvement. We finished Third in the Jet Silver race with a time of 408.286 mph and got a very nice trophy at the awards banquet.

As our week had gone on I was asked frequently about “next year.” Everyone assumed I’d be seeking a faster airplane and putting together a new team. I truthfully said that I have to get this set of races completed with consistency and avoiding errors of procedure and technique before I can worry about next year. I am not trying to say I am special and I wrote this article because I was asked to by the Racing Jets folks to explain what the experience of racing jets was like for me and my team. Without exaggeration this was one of the most fun and satisfying things I have done in my life.

Nathan Harnagel Pilot Page